The Smallpox Hospital, aka Renwick Ruin, on Roosevelt Island, NYC - Part 1

We take a look at the ruins of a forgotten Gothic hospital on Roosevelt Island in New York City

A crumbling ruin is all that’s left of the old Smallpox Hospital that used to operate on Roosevelt Island, an island that lies between Manhattan and Queens in New York City. Nowadays, the ruin lies in a park and is lit up by floodlights at night. It’s a picturesque shell of the old Gothic building, and is popular with urban explorers, but the story behind it is a fascinating one.

Originally built by James Renwick Jr, the superstar 19th century architect who built St. Patrick’s Catherdral in Manhattan, and often called “the Renwick Ruin” these days, the old Smallpox Hospital was built in the 1850s.

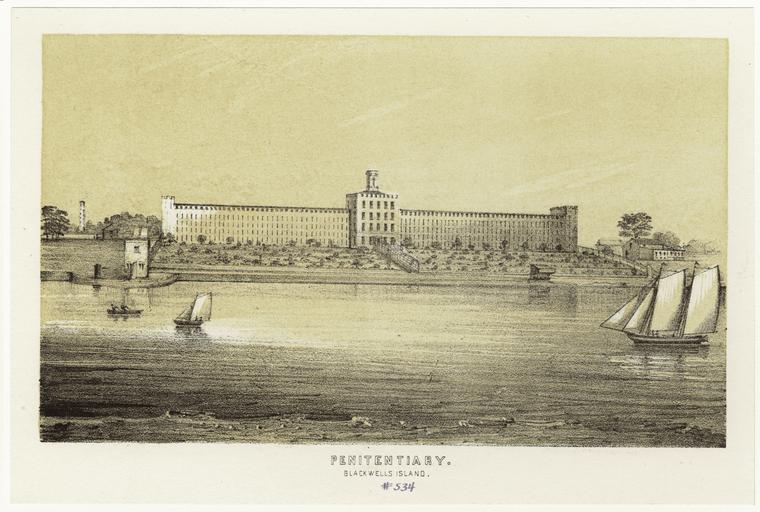

At the time, Roosevelt Island (then called Blackwell’s Island) was an isolated “haven” for the poor and sick–many wealthy Manhattanites wrote about the picturesque island, more garden than prison. But in reality, the island housed an infamous penitentiary (where William Macy Tweed, aka Boss Tweed, was once held), a workhouse and almshouse for the poor and sick, the infamous New York Lunatic Asylum (where muckraking journalist Nellie Bly got herself admitted to expose the horrific conditions), as well as a few hospitals, including the Smallpox Hospital.

In part one of our two-part look at the Blackwell’s Island Smallpox Hospital / Renwick Ruin, we talk about the history of Roosevelt Island and the hospital itself, as well as a bit of the history of smallpox in the world and in New York City. We’re coming to you from lockdown in Queens, New York, so we also talk a bit about how 19th century Blackwell’s Island relates to the world today, especially with the current coronavirus crisis. We also talk about about some paranormal investigations we want to do on Roosevelt Island once we’re cleared to hang out again.

Important Note: In the episode, we talk about wanting to do a paranormal investigation at the hospital. To be clear, we want to do an Estes session from outside the ruin’s fence. If you’re in the area, you definitely shouldn’t attempt to enter the hospital ruin itself–the floorboards are very unstable and crumbling, and breaking into the hospital could be extremely dangerous, even fatal. Like us, try to content yourself with looking at it from the outside and watching videos of the interiors from experienced urban explorers.

Roosevelt (Blackwell’s) Island in the 19th Century

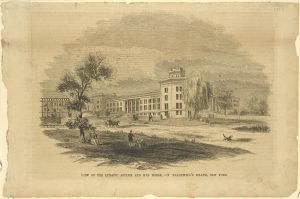

“View of the lunatic asylum and mad house, on Blackwell’s Island, New York” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1853.

Episode Script for The Smallpox Hospital, aka Renwick Ruin, on Roosevelt Island, NYC – Part 1

DISCLAIMER: I’m providing this version of the script for accessibility purposes. It hasn’t been proofread, so please excuse typos. There are also some things that may differ between the final episode and this draft script. Please treat the episode audio as the final product.

- “Located at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island, this fine Gothic Revival structure was originally constructed for the treatment of that “loathsome malady,” smallpox, and for many years was New York City’s only such institution. It is now a picturesque ruin, one which could readily serve as the setting for a 19th century “Gothick” romance.

… The Smallpox Hospital could easily become the American equivalent of the great Gothic ruins of England, such as the late 13th century Tintern Abbey in Monmouthshire, which has been admired and cherished since the 18th century as a romantic ruin. Plans have been made to transform the southern tip of Roosevelt Island into a park; ruins in park settings were so much enjoyed in Europe in the 18th century that small “garden fabrics,” which were purely ornamental structures, were actually built “in ruins” on various estates. The Smallpox Hospital in park surroundings would be of comparable picturesque interest. Paul Zucker in Fascination of Decay (1968) stated that ruins can be “…an expression of an eerie romantic mood… a palpable documentation of a period in the past… something which recalls a specific concept of architectural space and proportion.” The Smallpox Hospital possesses all these evocative qualities.”

-1976 Landmark Preservation Commission Report on the Renwick Smallpox Hospital on Roosevelt Island, New York -

- Renwick Smallpox Hospital, aka The Smallpox Hospital, later the Maternity and Charity Hospital Training School, and now generally known as The Renwick Ruin

- It’s located on what’s now called Roosevelt Island, but what at the time was called Blackwell’s Island.

- Roosevelt Island is an island that lies on the East River, between Manhattan and Queens. If you’ve seen the Toby Macguire Spider-man movie, then you’ve seen the tram that goes from Manhattan and Roosevelt Island. It’s also reachable via subway (the F train), and by a drawbridge from Queens.

- I’m interested in Roosevelt Island because I spend a lot of time looking at it from the Queens waterfront, especially these days. I’ve walked across the drawbridge from Queens countless times, and been on the tram a handful of times.

- We visited the Renwick Ruin twice last year, and that’s how I became interested in it

- Right now, it’s literally a crumbling ruin. It sits behind a chain-link fence right outside a park, and at night, it’s lit by spotlights. It’s very creepy and fascinating/beautiful.

- I really want to do some ghost-hunting nearby, like an estes session etc, but I think that’s gonna have to wait till things settle down.

What is smallpox?

- It was a highly infectious disease spread by airborne inhalation of the virus (so from droplets from infected people.)

- So usually it was spread by face to face contact with someone. It didn’t spread as fast as it might have, since you had to be interacting with an infected person for a decent amount of time, and b/c it wasn’t infectious until after the infected person already had the rash.

- As far as they knew, there wasn’t such a thing as an asymptomatic carrier stage.

- The first smallpox inoculations were used in India, Africa, and China.

- There are some ancient Sanskrit texts that describe the inoculation, and there are records of it being used in 10th century China, and by the Ming dynasty (the 16th century), it was in common use.

- Basically, the inoculations introduced a less deadly strain of the virus into the patient, and the idea was that they’d get immunity. However, one in five people got full blown smallpox and died or spread it to others.

- In the 1700s, the practice was brought to Europe and America.

- The English used smallpox as biological warfare during their genocide of the indigenous people of what’s now the United States. It’s confirmed that the leadership in the British military all condoned and approved the practice.

- There’s also some records indicating that smallpox was used as a biological warfare agent by the British in Australia, in New South Wales, though some people said it was chickenpox. Either disease would have been equally deadly to the aboriginal population.

- Then, in 1796, an English doctor figured out that people could be vaccinated more safely using cowpox.

- That’s actually where the word vaccine comes from: vacca is Latin for cow.

- Then, in the 19th century, a different strain of the virus started to be used.

- Over the years, as more and more people were vaccinated, smallpox was eventually eradicated.

- The last case of smallpox was in 1973, and nowadays the only people who get the vaccine are laboratory workers who may be exposed to smallpox in the course of their work.

- Some famous people who contracted smallpox include (not all of these people died of it):

- Lakota Chief Sitting Bull (who’s famous for leading resistance against the US government’s horrific policies. he didn’t die from smallpox; he was killed by police at Standing Rock in 1890)

- the 10th ruler of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan (who led the resistance against the Spanish invasion, and died of smallpox in 1520, shortly after it was introduced to the Americas)

- Ramses V (who lived in the 1100s, BC)

- three emperors of China, (one in the 1700s, one in the 1600s, and one in the 19th century)

- one emperor of Japan (19th century)

- a king of Spain, an Emperor of Russia, a king of France, a prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire, some British royalty including Elizabeth I, American presidents including George Washington, Andrew Jackson, and Abraham Lincoln. Also, Joseph Stalin

- one interesting anecdote: Catherine the Great of Russia didn’t get it, but her husband had a really bad case, and she worried about her son getting it so much that she socially isolated him and kept him away from large crowds. Eventually, she and her son got the vaccination, and then tried to vaccinate as many people as possible in the Russian Empire: 2 million people were vaccinated because of her efforts

- And that’s all I’m gonna say about it! Not talking about symptoms or anything, because everyone’s freaked out enough about coronavirus rn.

So, now that you know a little bit about the impact of smallpox, let’s talk about the hospital:

- Designed by James Renwick, Jr.

- he was kind of a kid-genius. He entered Columbia University at the age of 12 and studied engineering. (Note: his dad, who was also an engineer, graduated from Columbia in 1807 and was later a professor of natural philosophy at Columbia.) Apparently he graduated 3 years later and started work as an engineer on the Eerie Railroad, and then worked on the Croton Reservoir and Croton Aqueduct.

- The Croton Aqueduct supplied water to NYC (it stretched 41 miles and used gravity to bring the water to the city.) It was a project that they undertook to bring water from upstate because the city supply was no good. In the late 1840s or early 1850s, the Croton Aqueduct actually started supplying water to Blackwell’s Island, where the Smallpox Hospital was built. (They had to lay lead pipe down below the East River to get it there.)

- He didn’t have any formal architecture training.

- His first commission as an architect was Grace Church, in Manhattan, which was built in 1843. It’s on 10th and Broadway and is done in the English Gothic style. He was just 25 years old.

- He did a lot of Gothic Revival stuff, including his most famous work, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, a famous cathedral in Manhattan, near Rockefeller Center. It’s one of the top tourist attractions in the city.

- He designed a number of college buildings, including a building for City College in NYC and some buildings for Vassar, in Poughkeepsie, including the Main Building. He also designed the first chapter house of St. Anthony Hall/Delta Psi, a secret fraternity that was started at Columbia (that building’s on 28th street).

- He designed the Charity (aka City) Hospital and Smallpox Hospital on Roosevelt Island; the main building of the Children’s Hospital on Randall’s Island; the Inebriate and Lunatic Asylums on Wards Island. He was also the supervising architect for the Blackwell Island Light, the lighthouse that still stands on the north tip of the island today.

- Renwick was buried in Green-wood Cemetery

Roosevelt Island History:

- In the 19th century, Roosevelt Island was called Blackwell’s Island. (Named after Robert Blackwell, who owned it.)

- New York City purchased it in 1828.

- The island is in the east river, situated about equidistant from both Manhattan and Queens (which in the 19th century was called Long Island.) And it’s just south of an extremely dangerous part of the East River called Hellgate, which was the site of the greatest loss of life in New York City until 9/11 when a ship caught fire and more than a thousand people drowned. Hellgate is said to be very haunted.

- originally there was a little wooded area on the East side (I think where the Insane Asylum ended up being built.) And it was said that there was a lot of fertile land for growing vegetable gardens.

- Blackwell’s Island was made of a lot of blue stone, which was suitable for quarrying and building buildings.

- According to the Roosevelt Island Historical Society, the stone that was quarried on the island was a billion-year-old type of stone called Fordham gneiss (pronounced nice.) It’s one of the three types of stones that Manhattan was made from, and it’s called Fordham gneiss because the stone’s above the surface in the Bronx. (And the Bronx was the home of Fordham manor, which is now my alma mater, Fordham University.)

- A lot of the buildings on the island, including the prison, were made from rubble masonry, which is exactly what it sounds like. It’s rough-hewn stone set in mortar, rather than equally-sized and shaped stones set in neat rows.

- The first city building built on the island was the prison, in 1832.

- All travel to the island went through the department of public charities and corrections.

- It was home to several sanatarium/isolation style hospitals, an insane asylum, a prison, a workhouse, and an alms house.

- A workhouse, or alms house, is basically a prison for poor people, where they’re put to work. Supposedly, there was a workhouse for “lazy” poor people who apparently needed hard labor to fix them (they’d committed small crimes like robbery, drunkenness, etc.) The way I read it described was that the workhouse was for people who were police prisoners, and the prison was for people who had gone to court.

- The alms house was supposed to be gentler, for people whose crime was being poor. But I don’t see much of a distinction between the two when reading the historical accounts, except that the almshouse what where old, sick people were sent, and the workhouse was where able-bodied people were sent. One article from the 1850s mentions that one of the things the people in the workhouse did was a lot of the “grading” or landscaping of the lsland. Apparently in 1850, workhouse laborers were paid for their work (between 50 and 35 cents per day) but payment was abolished a few years later, supposedly because the administrators thought they’d just spend all the money on alcohol.

- In 1847, the alms house housed 902 people (760 of them were immigrants, 142 of them were born in the US.) They worked as nurses and housekeepers, at the bakehouse that supplied bread for all of the institutions on Blackwell’s Island and nearby Randall’s Island, washers and ironers, carpenters, tailors, blacksmith, boatmen, cartmen, and wool pickers. 435 of them weren’t able to work.

- Many of the original buildings on the island were built from stone quarried on the island, including the prison. The manual labor used in building the prison was done by prisoners (135 of them, some of them in chains.)

- Much like today, prisoners were used for anything the powers that be wanted to save money on: For a while, until around 1855, prisoners also worked for the Insane Asylum, doing indoor and outdoor work, attending patients, etc. Then they decided that maybe that wasn’t such a good idea and hired “responsible persons” instead.

- Some prisoners worked as boatmen, and some of the female prisoners worked in the sewing shop. Many prisoners did landscaping and gardening (from Harper’s Weekly in 1859):

- I read a really interesting article in a newspaper called Liberator, from 1842, about the prison at Blackwell’s Island that really rang true to me:

- It seems like in NYC, if we don’t want to have to think about something, we put it one an island. Examples:

- Riker’s

- Hart Island

- North Brother Island (sanitarium/rehab center)

- Fresh Kills Landfill on Staten Island

Now, onto the hospital

- We talked about how smallpox inoculation had been around for hundreds of years, and the vaccine came about at the end of the 18th century. So why did people in 19th-century NYC still have smallpox?

- One reason was that people didn’t get the vaccines because they didn’t trust the government.

- To be fair, there wasn’t clean water, the streets were full of rotting animals, and the city government was extremely corrupt, so it’s not that surprising that people didn’t trust them.

- Cases of smallpox actually went up in the 1850s in NYC, and smallpox killed 25-30% of the people who got it.

- Rich people were usually treated at home (which contributed to the spread of smallpox) and poor people were treated in wooden shacks along the East River called “deadhouses.”

- Medical professionals realized that people with smallpox should be isolated to prevent the spread of the disease.

- Since it was isolated–literally an island–Blackwell’s Island was an ideal place to keep contagious patients

- Opened in 1856

- It was built in the Gothic Revival style, out of blue stone quarried on the island. It was built for $38,000, which was very cheap at the time. It was really beautiful on the outside, with a crenellated roof, a grand entrance portico, unusual triangle-shaped windows on the 3rd floor, and a huge tower on top.

- Contemporary accounts said that the interior furnishing were excellent, but didn’t elaborate much. I watched some videos of urban explorers going through the ruins, and saw some ornate wrought-iron stair bannisters, and some tile-lined rooms.

- There was room for 100 patients, and it was the only hospital in New York dedicated to just smallpox patients. (It was also the only hospital that treated smallpox patients. By law, all smallpox patients in NYC had to be taken there to be quarantined.)

- The Smallpox Hospital admitted paying patients and charity cases (non-paying patients)

- Charity cases were put in the lower floors, and paying patients had private rooms in upper floors. If you were able to pay, you were required to pay. You could pay $5-10 per week for better food.

- Visitors were forbidden, but people were paid to carry letters from the dock to the hospital.

- There were also a few smaller hospitals:

- At some point, in addition to the Smallpox Hospital, there was a Fever Hospital, and Epileptic and Paralytic Hospital, a Scarlet Fever Hospital, a Relapsing Fever Hospital. Many of these smaller hospitals were housed in tents.

- Some of them were housed in wooden buildings around it, just by the water’s edge, dedicated to patients with typhus and ship fever (also known as typhoid fever). Those buildings could also hold 100 people, but apparently there were often more.

- Though conditions were bad, there were few other places where people with contagious diseases could go for treatment.

- About 10,000 patients were treated there in the 1850s and 60s. The hospital got mixed reviews.

- According to the Roosevelt Island Historical Society, which had some great details on their website, the NYT decried the terrible conditions in the hospital, saying it was poorly ventilated, killing many patients, and that it was little better than a shanty. Seven or eight patients might be stuck in a room with only one bed, and infected linens and clothes were reused without washing.

- However, apparently the NYT also praised the care that patients received there, saying the doctors and nurses were excellent.

- The Commission of Charities and Correction ran it at first.

- Talking about treatments at the Smallpox Hospital:

- An article from 1875 talked about treatments at the hospital: they mostly treated symptoms (like fever, insomnia, etc), and strongly recommended that everyone get vaccinated. You could get smallpox multiple times, so they recommended getting vaccinated multiple times.

- From Harper’s Weekly, in 1869:

- Then in 1875, the Board of Health took it over.

- The hospital was only 20 years old, but was starting to get run down, and patients were reluctant to go there.

- So they tried to rebrand it, calling it “Riverside Hospital”

- They also replaced the open-air “sick wagon” that brought patients to the dock to go to the island with a closed carriage.

- They also brought in the Sisters of Mercy from the St. Vincent Hospital to clean up the hospital.

- The city report said:

- “Since the change in management…the hospital has been steadily gaining in popularity, and it is not at all unusual for us to be gratified with the sincere thanks of returned patients for the kindness and tender care which they received during the period of exclusion from their homes and from society….”

- However, in the late 1870s or early 1880s, they moved the smallpox patients to North Brother Island, a smaller and more isolated island off the coast of the Bronx. Some sources said that they did that because the patients could be more isolated and so the growing population of Blackwell’s Island didn’t have to risk infection. Some said that fewer people were getting smallpox, and there was a new-and-improved cowpox farm in Manhattan that was providing tons of vaccines for everyone.

- To give you a quick overview of the future of smallpox in NYC after that:

- In the 1870s, there was another smallpox epidemic that killed 1,200 people.

- In 1900, it came back and killed 700 people.

- By 1902, the Health Department was vaccinating 10,000 New Yorkers every day.

- Smallpox didn’t return to NYC until 1947, but the city acted quickly, and within 2 weeks, 5 million people were vaccinated. Only 12 people got smallpox that time, and only 2 people died.

- In 1967, there was a movement to end smallpox for good, and they were successful.

- So around the 1880s, the Smallpox Hospital became nurses’ housing and a training school affiliated with the much larger Charity Hospital, which was just north of the Smallpox Hospital, and which Renwick also designed (after an earlier version of the building burnt down).

- Having professional, trained nurses was still a rarity at the time, so this was a game-changer.

- The program was for 2 years, and women between 20-25 years old could join, as long as they had certificates attesting to their moral character and health.

- They did basic things to help the patients, like change sheets, take temperatures, etc. And they also took classes. a few of them were called: “Poisons and Antidotes,” “Pulse, Respirations, Temperature, Bandaging,” and “the Application of Leeches and Subsequent Treatment.”

- In 1903, a south wing was added, and in 1904, a north wing was added.

- Want to talk a bit about the Charity Hospital, because it actually relates a lot to current events today:

- It was initially called Penitentiary Hospital, then Island Hospital, then Charity Hospital, then City Hospital.

- The book Damnation Island talks about how in the mid-19th century, if you were poor and had syphilis , the only place you could be treated was at the penitentiary hospital. So if you went in for medical care and they found out that you had syphilis, they shipped you off to the police court. If you wanted treatment, you had to voluntarily commit yourself to the penitentiary for vagrancy, and then they’d send you to the hospital, which at the time was at the top floor. The police would decide how long your sentence was, and you were treated like the rest of the criminals.

- From an 1866 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article, it sounds like some people treated at “the Island Hospital” had to serve in the penitentiary as payment for medical care.

- Even children had to go to jail to get care for syphilis. There was a story about a 12-year-old girl in treatment at the penitentiary hospital. By the way, since antibiotics hadn’t been invented yet, people were treated with mercury, which is obviously deadly.

- In 1846, Dr. William W. Sanger was put in charge of the hospital, and said that not everyone with syphilis was a criminal. (He gave the example of how a poor woman could catch it from an unfaithful husband, or a drunken laborer could catch it from a sex worker.) Sanger also lead a survey of 2,000 sex workers and ended up calling to decriminalize sex work and to have a medical bureau in the police department monitor sex workers for health issues and hospitalize them when they were infected.

- Sanger was able to do a little bit of reform in the hospital before he resigned in 1847. But he returned in 1853.

- While he was gone, a new hospital building–which he had advocated–had been built. But it was so badly constructed that it was considered unsafe for people to enter. However, since Sanger was gone, patients were put in the hospital anyway.

- During his second stint, he was able to change the rules so people could get treatment without first needing to be convicted of a crime. He also got the name changed to Island Hospital.

- On February 13,1858, during a terrible snowstorm, the unsafe Island Hospital building burned down. There were fire hydrants on the island, but they weren’t working, and there wasn’t a fire department on the island. So people–mostly convicts–just had to throw buckets of water from the river on the fire.

- Shockingly, no one died during the fire, even though everyone had been locked inside. The walls of the hospital collapsed.

- Everyone was pretty happy that they had a chance to build a new hospital.

- When the Renwick version of Charity Hospital was built, convicts from the island quarried the stone that was used in the walls.

- When the cornerstone of the Renwick version of Charity Hospital was laid, the president of the almshouse board of governors, called Blackwell’s Island “this New York Garden of Charity.” And he described the patients “victims of pollution, brought on by shame and crime.” Not much has changed.

- The cornerstone has a copper box “with coins, hospital documents, newspapers and drawings of the hospital and other memorabilia.”

- A New York Times article from 1994, right before the new hospital’s ruins were torn down, described the ruins of the hospital as “a rough, dark gneiss that might have been used on a Dickensian prison.” However, an article from the Episcopal Recorder 1858, when the cornerstone was laid, described it as consisting of “pearl-colored stone quarried on the island.”

- The hospital was supposed to cost $400,000 to build ($300,000 more than the original hospital that burned down.) But it ended up being estimated to cost $150,000 since they used prison labor.

- From Harper’s Weekly in 1859:

- (missing words are “prepared to in case of insubordination, to shoot down, half”

- The hospital was the largest hospital in New York. It was built in the Second Empire style, and it had a mansard roof. (It was a similar style to the one Renwick used for the Vassar Main building.) It was three and a half stories tall, and was almost as wide as the island.

- It had 29 wards, ranging from 13-39 beds each.

- Though the hospital was finished being built in 1861, people started using it in 1860, which was also the year that Sanger left.

- Once he left, prison wardens once again took control of the hospital, instead of doctors. All of the medical departments were run by recent med school graduates who didn’t know how to do anything, and real doctors only visited once a week.

- During and after the Civil War, injured veterans were treated at the hospital.

- In 1866, they changed the name of the hospital to Charity Hospital.

- It’s pretty gruesome: recovering patients were made to work, and in 1867, patients made 504 shrouds. Reports from the time don’t say that the shrouds were for other patients, but 505 people died at the hospital that year.

- In 1869, a patient from Charity Hospital was the first person buried in the new potter’s field on Hart Island.

- Hart Island has been in the news a lot lately, because it’s still an operating potter’s field, with labor done by prisoners. It’s where unclaimed bodies in NYC are buried nowadays, and it’s the place where the city’s pandemic plan says that bodies will be buried if there’s a large number of coronavirus victims.

- Conditions were bad; the chief of staff reduced the amount of food that patients were given, several patients killed themselves and at least one staff member murdered a patient.

- But soon after, doctors were put back in charge of the hospital, and heating and ventilation was installed.

- Also, as soon as enough nurses were trained at the nearby nurses school, in what used to be the smallpox hospital, the nurses started tending to the patients. They were really nice and kind to patients, and reported abuse from any other workers immediately.

- There were also some good doctors. The chief of staff, Dr. Curtis Estabrook, who was from Canarsie, in Brooklyn, was so beloved that the people of Canarsie tried to have the neighborhood’s name changed to “Estabrook.”

- Also, a couple years after the nurses’ school was established, the British surgeon Joseph Lister, who’s known for introducing and advocating for antiseptic surgery, visited Blackwell’s Island and trained the medical staff on how to sterilize everything used in surgery.

- Charity Hospital became known for their adherence to sterilization; they even had a special room for sterilizing items.

- In 1892, Charity Hospital was renamed City Hospital.

- In 1957, City Hospital was relocated to Queens. Apparently, Charity Hospital was actually moved to Elmhurst Hospital Center, which is now the a big symbol of the coronavirus pandemic.

- One thing that inspired me to start doing this research is everything I’ve been reading about Elmhurst; I’ve been thinking a lot about how we live right in between the ruins of the smallpox hospital, and the bustling center of our current pandemic. City Hospital was the second-oldest charity hospital in the city, and it served the poor. Elmhurst Hospital Center also serves a lower-income, immigrant population.

- Even in the late 1970s, Elmhurst hospital has a shortage of nurses and ICU beds, and three patients who were on respirators died. There was a murder investigation to look into it, but doctors said it was just the lack of staff and beds.

- In 1921, Blackwell’s Island was renamed to Welfare Island as part of an effort to rehabilitate the island’s image.

- In the 1930s, there were a number of scandals related to the terrible conditions in the prison on the island, and eventually a raid exposed the conditions in the prison.

- The prison and the workhouse were torn down in 1936, and the prisoners were moved to a new prison on Riker’s Island, where they remain today.

- Rikers is famous for being one of the worst prisons in the US. By 1939, it was so overcrowded, dangerous, and unsanitary that a court in the Bronx called it “nearly unlivable.” And as early as 1941, the number of incarcerated black people started to skyrocket, creating the system of mass incarceration of black folks that continues today.

- There are so many horrific stories about what happens in Rikers. For example, in 2010, a sixteen-year-old kid named Kalief Browder was arrested for stealing a backpack and was put in Rikers for 3 years without a trial, two of those in solitary confinement, and he was also subject to abuse from guards and inmates. His case was dismissed in 2013, but he was deeply traumatized, and he died by suicide in 2015.

- In the 1950s, many of the hospitals were closed down and a lot of the island was abandoned.

- In the 1960s, plans were made for housing to be made there, and in 1969, residential development began. Most of the 19th century buildings were torn down so they could build new construction.

- In 1973, Welfare Island was renamed to Roosevelt Island.

- One of the hospitals that remained on the island was built on the former site of the penitentiary. That hospital, Goldwater Memorial Hospital, started out being really beautiful and modern. But because of budget cuts, it became so bleak that part of The Exorcist was filmed there. It was torn down in 2015, and now there’s a Cornell Tech campus there.

The Ruin

- In 1972, the architect who oversaw the shoring up of the Smallpox Hospital inspected the old City Hospital building and said it was in good condition. It sounds like they planned to turn it into apartments. But the building wasn’t guarded, and vandals set fires that basically destroyed the building, leaving the building just a shell, much like the Smallpox Hospital.

- Apparently, in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, people considered making it a landmark. Eventually, in 1994, the ruins of City Hospital were torn down, because they felt that the large building would be too difficult to repurpose.

- After tearing down they hospital, they saved the stones and use them when building the park at the tip of the island, Southpoint Park. It also said that they had found out about the copper box in the cornerstone after demolition had already started, and it was unclear if they were ever able to save it.

- During the 1970s, the Smallpox Hospital fell into severe disrepair. In 1975, there was a preservation effort to save the exterior walls, though there wasn’t any attempt to prevent collapse or decay in the rest of the building.

- It’s been designated a national historic landmark.

- Now, all you can see are the exterior walls, which are made of gray gneiss, and the brick foundation. On the inside, the wooden floors have almost rotted through, and several stories collapsed.

- It sits behind a chain link fence.

- There’s no roof left

- It’s propped up by lumber struts

- Part of the remaining ruins, the north wall, collapsed in 2007

- It’s lit up at night.

- From a 2008 NYT article: “There’s not much holding up the cornice right now,” said Judith Berdy, president of the Roosevelt Island Historical Society. She said she feared the effects of freezing and thawing on the already weakened masonry.

- In 2009, a new park, Four Freedoms Park, was built on the southern end of Roosevelt Island, just south of the Ruin. Supposedly, there’s a $4.5 restoration project planned for the Ruin.

- For a while, a few years ago, there was talk of tearing down the ruins of the Small-Pox hospital; I’d even heard it was torn down at one point, and was sad that I hadn’t seen it beforehand. But they thankfully decided against it.

Sources

These sources were used for parts 1 and 2 of the episode on the Renwick Ruin.

Books

Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad & Criminal in 19th Century New York by Stacy Horn

Websites

- Great pictures of City Hospital

- Pictures of student nurses working on Blackwell’s Island

- Landmark commission report on Renwick Ruin

- Paris Review article about the ruin

- Wikipedia article about smallpox

- Wikipedia article about James Renwick Jr.

- Wikipedia article about hospital

- Wikipedia article about Croton Aqueduct

- NYC drinking water history

- Renwick on Columbia University website

- Renwick’s findagrave.com page

- Yelp page

- Another Wikipedia article about hospital

- Haunted asylyms on Curbed

- Roosevelt Island Operating Corporation

- Urban Explorer video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5ya_6vhMl0

- The Ruin – great site about this

- NYT article from 2008

- NYT article from 1994

- Wikipedia article about Elmhurst Hospital Center

- Wikipedia article about rubble masonry

- Wikipedia article about Blackwell Island Light

- Roosevelt Island Historical Society blog post

- Roosevelt Island Historical Society – Blackwell’s Almanac August 2015

- Roosevelt Island Historical Society – Blackwell’s Almanac Nov 2015

- Roosevelt Island Historical Society – Blackwell’s Almanac May 2018

- Fordham Gneiss (EPA site)

- CorrectionHistory.com – Blackwell’s Island Part 1

- CorrectionHistory.com – Blackwell’s Island Part 3

- Southpoint Park – michaelminn.net

- Great Springer article about this

- Untapped Cities – pics

- Daily News Article about “Damnation Island”

Articles

- National Philanthropist, Date: January 9, 1829, “Blackwell’s Island”

- Peabody’s Parlour Journal, 2/1/1834, Vol. 1 Issue 5, p2-2, 2/5p, 1 IllustrationIllustration; found on p2

- Blackwell’s Island Prison. Youth’s Cabinet. 6/27/1839, Vol. 2 Issue 26, p101-102. 2p.

- Blackwell’s Island. New-York Organ & Temperance Safeguard, Date: August 26, 1848

- Drunkenness at Blackwell’s Island. New-York Organ & Temperance Safeguard. September 9, 1848

- “Penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island, New York.” Journal of Humanity & Herald of the American Temperance Society. 07/08/1829, Vol. 1 Issue 7, p28-28. 1/5p.

- “HOSPITALS ON BLACKWELL’S ISLAND, NEW YORK.” Boston Medical & Surgical Journal. 11/10/1847, Vol. 37 Issue 15, p300-302. 3p.

- “The Prison at Blackwell’s Island” By: L. M. C. Liberator. 10/28/1842, Vol. 10 Issue 43, p172-172. 1/5p. , Database: Slavery and Abolition, 1789-1887

- “CASES AT THE PENITENTIARY HOSPITAL ON BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” CLAUDIAN (AUTHOR). Boston Medical & Surgical Journal. 8/16/1848, Vol. 37 Issue 2, p57-60. 4p.

- “STATE OF PRISONERS ON BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” ERBEN, HENRY. New York Municipal Gazette. 03/02/1846, Vol. 1 Issue 38, p527-527. 1/6p. , Database: American Literary Periodicals, 1835-1858

- “Blackwell’s Island.” American Statesman. 07/31/1847, Vol. 1 Issue 26, p408-409. 2p. , Database: American Political Periodicals, 1715-1891

- “Doings at Blackwell’s Island.” New-York Organ & Temperance Safeguard. 12/02/1848, Vol. 8 Issue 23, p180-180. 1/9p.

- “The New Work-House on Blackwell’s Island.” Friend: A Religious & Literary Journal. 12/7/1850, Vol. 24 Issue 12, p90-90. 1/3p.

- “No. 12.–NEW YORK. Criminal and Humane Institutions.–Police.–Workhouse on Blackwell’s Island.” Pennsylvania Journal of Prison Discipline & Philanthropy. 1851 1st Quarter, Vol. 6 Issue 1, p59-60. 2p.

- “CROTON AQUEDUCT SUPPLY OF WATER TO BLACKWELL’S ISLAND BY MEANS OF GUTTA PERCHA PIPE.” C. (AUTHOR). Appleton’s Mechanics’ Magazine & Engineers’ Journal. Dec1851, Vol. 1 Issue 12, p738-741. 4p.

- “SUPPLY OF WATER TO BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” Friend: A Religious & Literary Journal. 11/27/1852, Vol. 26 Issue 11, p82-83. 2p.

- “ALM HOUSE, BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” Gleason’s Pictorial. 10/09/1852, Vol. 3 Issue 15, p225-225. 1p. 1 Illustration, 1 Graphic, Symbol or Logo.

- “PENITENTIARY, BLACKWELL’S ISLAND, NEW YORK.” Gleason’s Pictorial (Boston, MA – 1853-1854). 05/28/1853, Vol. 4 Issue 100, preceding p338-338. 1p. 1 Illustration, 1 Graphic, Symbol or Logo.

- “LUNATIC ASYLUM, BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” National Magazine. Oct1855, Vol. 7 Issue 4, p314-315. 2p. 1 Illustration.

- “Randall’s and Blackwell’s Islands.” Independent (New York, NY 1848-1876). 09/27/1849, p172-172. 1/9p.

- “BURNING OF BLACKWELL’S ISLAND HOSPITAL.” Brother Jonathan (New York, NY). 2/20/1858, Vol. 17 Issue 327, p003-003. 1/9p.

- “BLACKWELL’S ISLAND HOSPITAL.” Episcopal Recorder. 8/7/1858, Vol. 26 Issue 19, p74-74. 1/9p.

- “A VISIT TO THE LUNATIC ASYLUM ON BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” Harper’s Weekly. 03/19/1859, Vol. 3 Issue 116, p184-186. 3p. 10 Illustrations.

- “THE WORK-HOUSE–BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. Nov1866, Vol. 33 Issue 198, p683-702. 20p. 19 Illustrations.

- “VISIT TO BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” FOSDICK. American Odd Fellow: A Monthly Magazine. Apr1869, Vol. 8 Issue 4, p208-211. 4p. , Database: Masons, Odd-Fellows and Other Societal Periodicals, 1794-1877

- “SMALL-POX HOSPITAL, BLACKWELL’S ISLAND, F. Y.” New York Medical Journal: A Monthly Record of Medicine & the Collateral Sciences. Feb1875, Vol. 21 Issue 2, p173-176. 4p.

- “PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS ON BLACKWELL’S ISLAND.” Harper’s Weekly. 2/6/1869, Vol. 13 Issue 632, p91-91. 1/6p.

- “SMALL-POX HOSPITAL.” Life Illustrated. 01/24/1857, Vol. 3 Issue 13, p101-101. 1/9p. , Database: Periodicals of the American West, 1779-1881

Images Used in this Post

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Blackwells Island, East River. From Eighty Sixth Street, New York” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1862. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-e879-d471-e040-e00a180654d7

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. “Penitentiary : Blackwells Island.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1840 – 1870. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-2793-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “Smallpox Hospital, Black Wells Island, N.Y.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1850 – 1930. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-208e-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “View of the lunatic asylum and mad house, on Blackwell’s Island, New York” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1853. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-d3cf-d471-e040-e00a180654d7