Victorian Egyptomania (Ouija Boards Part 5)

We take a detour in our look at the Ouija board and dive into Victorian Egyptomania.

In the Victorian Era, people were really into death and the supernatural. Americans and Europeans also started traveling to Egypt and bringing back mummies and other pieces of Egyptian culture. We talk about some of the weird stuff that Victorians did with Egyptian artifacts, some now-destroyed Egyptian Revival buildings in NYC, and more, as well as what all of this has to do with Ouija.

Highlights include:

• An Egyptian Revival prison built on quicksand in New York City

• Mummy unwrappings

• Creepy automatons and mad scientists

• Mummies as medicine

• Jewelry made from real scarab beetles

• Imperialism and stealing Ancient Egyptian artifacts

• Indiana Jones-style hijinks

• A giant Egyptian-influenced reservoir that used to sit in the middle of midtown Manhattan

Photo of the Croton Reservoir covered in ivy (from Ephemeral New York: https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2009/06/14/when-the-citys-water-supply-came-from-42nd-street/ )

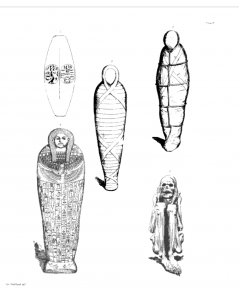

Image from A History of Egyptian Mummies

By Thomas Joseph Pettigrew

Image from A History of Egyptian Mummies

By Thomas Joseph Pettigrew

Image from A History of Egyptian Mummies

By Thomas Joseph Pettigrew

Image from A History of Egyptian Mummies

By Thomas Joseph Pettigrew

Episode Script for Victorian Egyptomania (Ouija Boards Part 5)

DISCLAIMER: I’m providing this version of the script for accessibility purposes. It hasn’t been proofread, so please excuse typos. There are also some things that may differ between the final episode and this draft script. Please treat the episode audio as the final product.

“This obelisk may ask us, ‘Can you expect to flourish forever? Can you expect wealth to accumulate and man not decay? . . . Can it creep over you and yet the nation know no decrepitude?’ These are questions that may be answered in the time of the obelisk but not in ours.”“

-US Secretary of State William Maxwell Evarts’s remarks when Cleopatra’s Needle, an obelisk in New York City’s Central Park, was raised

- Today, we’re talking about the Victorian obsession with all things Egyptian.

- I think that a big part of Victorian Egyptomania is tied in with Victorian ideas about death and interest in the supernatural.

- However, I did want to talk some about the racial component to Egyptomania–beyond the obvious imperialism involved in Europeans and Americans stealing artifacts from Egypt.

- But there’s been scholarly work done that unpacks the racial implications of of Egyptomania in the US–the US definitely seemed to see America as a powerful empire like the Egyptian one. And there’re parallels between Egypt and the US in that they’re empires built on slavery, and that the conflict about the freedom of slaves (the Civil War and beyond in the US, and Exodus in Egypt) were defining moments.

- I wanted to read a bit from the summary of a book on the topic, Egypt Land by Scott Trafton:

- “The American mania for Egypt was directly related to anxieties over race and race-based slavery. . . . the fascination with ancient Egypt among both black and white Americans was manifest in a range of often contradictory ways. Both groups likened the power of the United States to that of the ancient Egyptian empire, yet both also identified with ancient Egypt’s victims. As the land which represented the origins of races and nations, the power and folly of empires, despots holding people in bondage, and the exodus of the saved from the land of slavery, ancient Egypt was a uniquely useful trope for representing America’s own conflicts and anxious aspirations.”

- And people were very aware of this parallel during the 19th century. A black 19th century doctor, writer, spiritualist, and Rosicrucian occultist named Paschal Beverly Randolph, said, in 1863: “For America, read Africa; for the United States, Egypt”

- A lot of black thinkers in the 19th century sought to show that Egyptians were black Africans–that would counter the racist and degrading history that the United States had imposed on African Americans.

- And I think pretty much everyone knows about how enslaved African Americans identified with Exodus, singing spirituals like “Go Down, Moses” where Israel stood for the enslaved African Americans, whereas the Pharaoh represented the slave master.

- And I guess it goes without saying that leading white scientists like Thomas Pettigrew, who we’ll talk about later, were meanwhile measuring mummy skulls and claiming that they were Caucasian rather than African.

- This is a huge topic and I’m not doing it justice, but I didn’t want to launch into the topic of Egyptomania without touching on that, since it’s such an important part of it.

- So the whole reason why I got the idea to do this episode as part of our Ouija series is that I came across and interesting tidbit about the naming of the Ouija board

- Someone on stackexchange posited that it may have come from a type of charm called the “oudja”–they found an article from November 1885 about it, saying it was an “Egyptian good luck charm.” Articles about the charm persisted through 1891–to quote from an 1891 article that they posted:

- The latest craze to strike Philadelphia is the wearing of the “Oudja,” a pretty little Egyptian charm, supposed to ward off all forms of evil. The charm is thin, and about an inch long and half an inch wide. A conspicuous figure is the eye of “Horus” which represents the sun, and a teardrop hanging oendant from the eyes that represents the river Nile. The little charm, which has been worn in England for a couple of years, has been indispensable to the superstitous Egyptians for many centuries.

- A pretty storey explains the Egyptian craze. A young officier in the English army sent one home to his bride, with an explanation of its origin. After a battle in the Soudan the young officier was reported dead, but his wife refused to believe it. Later on the official dispatches confirmed the death, but still the bride had faith in the little charm. Several months later the missing husband turned up alive and well, and the “Oudja” became a fad of great proportions.

- Also, note: there’s a large city in Morocco called Oujda or Wejda, so I wonder if that could have also influenced the name of the board

- So, the other reason why I think this is relevant–aside from the theory that the Ouija board’s name could have had a North African influenced origin is that I feel like Egyptomania is tied in with the obsession with death and the spirit world that caused Ouijamania. I also think it has some bearing on the Ouija board’s popularity, since it was marketed as an Egyptian luck board, and seemed exotic and magical.

- So to set the state, I wanted to define the Victorian period of history, since we’ve mentioned it some without really talking about exactly when it was and what it was like.

- So just a quick reminder: The Victorian Era stretches the length of Queen Victoria’s reign, which went from 1837 until 1901. It might be my favorite historical period because it’s so weird.

- The Georgian era, the period right before the Victorian era, was all about rationality and science, etc. (That spanned from 1714-1837, and was during the reign of 4 kings named George.) Jane Austen wrote during the Georgian Era, so that’s always my reference point for it. But of course the Georgian era was also the time of the Enlightenment, and other kinda boring sciency advancements.

- So the Victorian era followed that, and really kinda went off the rails. The Victorian era is prob best known for being this really buttoned up, repressed, religious time, but there was also a new interest in mysticism and the occult.

- As the 19th century wore on, things got weird.

- Gothic literature became popular again. Frankenstein was written during the Georgian period, but in the Victorian era we got awesome stuff like Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella Carmilla, about a lesbian vampire. Also Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Grey, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In America, we had Edgar Allen Poe writing in the US in the mid-19th century. So it seems unavoidable that the morbid Victorians would get really into Egyptomania.

- Gothic Revival architecture, which began in the 1700s, began to really proliferate in the 19th and early 20th century.

- One important tidbit that I learned while doing this bit of research is that Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, got really interested in Egyptology in the 1880s, and he corresponded with Oscar Wilde’s father, Sir William Wilde, who was a noted cadaver collector.

- One Egyptomania-related anecdote that really nicely illustrates the shift from the Georgian to the Victorian era is a building called the Egyptian Hall, which once stood in Piccadilly in London.

- Built in 1812, during the Georgian Period, Egyptian Hall is a byproduct of a new interest in Egypt. That interest began in part because in 1798, Lord Nelson–who was a huge British hero–won the Battle of the Nile, one of the battles in the Napoleonic Wars.

- Also, Napoleon himself stole a bunch of Egyptian artifacts and brought them back to Europe.

- These pieces quickly became popular among the European upper classes, and people became really interested in the “exotic” and “mysterious” Egyptian aesthetic.

- So when you walked into Egyptian Hall, the entry hall was a replica of the avenue at Karnak (which was a temple complex in the ancient city of Thebes, near Luxor–which fans of the Mummy Returns may recognize).

- The facade of the Egyptian Hall really exemplified the Egyptian revival style, looking almost like an Egyptian temple, complete with huge columns and sculptures of people on the front.

- For a while, Egyptian Hall held natural history specimens from Captain Cook’s voyages in the South Seas. Later, Napoleonic War relics were displayed there.

- Then a man named Giovanni Battista Belzoni took over the building. To read from georgianlondon.com:

- An Italian strongman and performer, with an English wife, Sarah, Belzoni was a true adventurer: in 1817, he travelled to the Valley of the Kings and broke into the tomb of Seti I. From Seti’s tomb, Belzoni took a sarcophagus of white alabaster inlaid with blue copper sulphate of great beauty. The retrieval of the sarcophagus, however, was not without peril: the tomb was located in the catacombs, a maze of traps and dead ends, dug to confuse grave robbers. The French interpreter panicked and an Arab assistant broke his hip in a booby trap. Undeterred, Belzoni retrieved the sarcophagus and brought it to England along with the head of the ‘Younger Memnon’. Belzoni suffered constant vomiting and nosebleeds in Egypt, whilst Sarah was unaffected by so much as a case of sunburn – much to her husband’s chagrin.

- In 1846, things got weirder: there was a really creepy exhibit of a talking machine, which was an automaton of a lady’s head attached to a bit machine on top of a piano. She had dark hair, in ringlets, and eyes that didn’t blink. Her name was Euphonia.

- She could say:

- “Please excuse my slow pronunciation… Good morning, ladies and gentlemen… It is a warm day… It is a rainy day… Bongiorno, signori.”

- The inventor was a sort of mad-scientist type who was described thusly by a man who knew him:

- The Professor was not too clean, and his hair and beard sadly wanted the attention of a barber. I have no doubt that he slept in the same room as his figure—his scientific Frankenstein monster—and I felt the secret influence of an idea that the two were destined to live and die together… One keyboard, touched by the Professor, produced words which, slowly and deliberately in a hoarse sepulchral voice came from the mouth of the figure, as if from the depths of a tomb.

- By 1873–deep into the Victorian Era–the Egyptian Hall had become a bit less respectable:

- The hall became known as the “England’s Home of Mystery”

- John Nevil Maskelyne, a magician and inventor, performed there for 31 years.

- His story is interesting: he got into stage magic when he saw some fradulent spiritualists perform, and realized that he could make all of the supposedly “magic” things happen without any actual magic.

- He was the inventor of several illusions that are still used by magicians today, including some stuff to do with levitation.

- He ended up running in the same circles as Harry Houdini, which makes since, since they were both magicians trying to disprove spiritualism as a fraud.

- He wrote a book called “Modern Spiritualism” and later founded a group called the “Occult Committee” to investigate the paranormal and disprove it.

- Fun fact: He also invented the pay toilet.

- Even though they were trying to disprove Spiritualism, Maskelyne once said:

- “…the Spiritualists had no alternative but to claim us as the most powerful spirit mediums who found it more profitable to deny the assistance of spirits.”

- Built in 1812, during the Georgian Period, Egyptian Hall is a byproduct of a new interest in Egypt. That interest began in part because in 1798, Lord Nelson–who was a huge British hero–won the Battle of the Nile, one of the battles in the Napoleonic Wars.

- So basically, by the 1890s, the Egyptian Hall was strongly associated with spiritualism and the occult.

- It was torn down in 1905, and a Starbucks stands in its place now.

- Okay, enough of that digression–I want to get to the main digression: Egyptomania!

- One note: when we were talking about Egyptian stuff a few weeks ago, I mentioned that people ground up mummies and used them as medicine. I’d thought it was a victorian thing, but apparently it was an earlier thing. People started doing it as early as either 1100 or 1300.

- Just a sidenote: I just want to take a moment to remind everyone that we’re talking about cannibalism, here. And all of Egyptomania is tied to something that I think’s even worse than cannibalism, which is plundering another culture and then taking its history–right down to the bodies of their ancestors–and commodifying them.

- The stories we’re telling here are weird and dark, and it’s hard not to laugh at how absurd they are–and I’m sure we’re going to laugh, because this stuff is bizarre and the Europeans and Americans who partook in Egyptomania were foolish and ridiculous. But I just wanted to give us a moment to reflect on how we’re talking about basically white people plundering a Egyptian culture and history.

- Okay, with that caveat aside, let’s talk about the use of powdered mummy as a medical remedy.

- It sounds like powdered mummy was an item that was sold to Christians (particularly in Europe), and that it became very popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. Apparently pretty much every apothecary carried it as a treatment for cuts and bruises.

- People broke into tombs and stole mummies.

- Though people also made fake mummies using the bodies of executed criminals and slaves, or people who’d died from different diseases, and then sold that to people as if they were ancient mummies.

- They also used the bodies of people who died while traveling in the desert, because the dry dessert air desiccated their bodies. The bodies of young women were supposed to work better for medicinal purposes, so they were more expensive.

- King Francis I of France, who was a king in the 1500s, carried around a pouch of powdered mummy mixed with rhubarb, and then anytime he tripped or fell, he took some mummy. You know, for health.

- So I got most of this information from a book from the 19th century called A History of Egyptian Mummies by Thomas Pettigrew. Based on what he wrote, it sounds like by the 19th century, this wasn’t as much of a thing anymore. But people were still obsessed with Egypt.

- Just a sidenote: I just want to take a moment to remind everyone that we’re talking about cannibalism, here. And all of Egyptomania is tied to something that I think’s even worse than cannibalism, which is plundering another culture and then taking its history–right down to the bodies of their ancestors–and commodifying them.

- But one thing that was big in the Victoria era was Egyptian themed mourning jewelry.

- Women would wear jewelry with real dried scarabs, or with Egyptian imagery lke obelisks.

- The Egyptian Revival style became popular in cemeteries:

- Highgate Cemetery in London has a huge gate done in the Egyptian revival style, as does Mt Auburn Cemetery in Boston, and Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, Connecticut.

- In Brookyn’s Green-wood Cemetery, you can see an Egyptian revival mausoleum.

- And of course non-cemetery Egyptian Revival structures were big:

- The Washington Monument, which is the obelisk in Washington, DC, was erected during the Victorian period

- There were also several large Egyptian Revival buildings in NYC that have since been torn down, including:

- the original 1938 version of the Manhattan Detention Complex, more often referred to as “The Tombs,” where prisoners go to wait for hearings.

- This original Egyptian revival building is how the Tombs got their name.

- The Tombs’ architect was inspired by a recently published travelogue that had an etching of an Egyptian Tomb

- The prison’s construction hit a snag, because the location was a filled in pond that had quicksand just beneath the surface of the ground; they had to make the foundation out of basically a raft that would rise and fall with the quicksand, which moved with the tides

- It had very few windows, for exterior aesthetic reasons, so there was so little light that the interior had to be lit by gas lights, even during the day

- The building was gloomy and dark, and Charles Dickens said of it: “What is this dismal fronted pile of bastard Egyptian, like an enchanter’s palace in a melodrama? . . . Such indecent and disgusting dungeons as these cells, would bring disgrace upon the most despotic empire in the world!”

- Eventually, the building was declared unsafe, and in 1897, it was demolished.

- The New York Times called it “the finest specimen of purely Egyptian architecture to be found in the United States.”

- Though they considered relocating the building to Central Park and repurposing it, that plan was deemed too expensive.

- In the end, no part of the building (which had some winged scarabs, beautiful columns, and other unique details) was preserved.

- Another now-forgotten Egyptian Revival structure in NYC was the Croton Reservoir, which stands where Bryant Park and the famous NYPL building are now

- When we talked about the Renwick Smallpox Hospital, we discussed how James Renwick, Jr., the architect of the Smallpox Hospital as well as more famous NYC buildings like St. Patrick’s Cathedral, worked on the Croton Acqueduct, which was constructed to bring clean water to the city. Specifically, he designed the Egyptian Revival Croton Reservoir.

- The Acqueduct brought water from Upstate New York, where it was stored in the reservoir and then distributed around the city. Before that, there had been some really horrific outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera because of a lack of safe drinking water.

- The Reservoir sat on four acres of land, held 20 million gallons of water, and built of huge granite blocks. It started distributing water in October 1842.

- Once it opened, people could visit the reservoir and go for walks around its edge–Renwick had designed a wide promenade, so people would go there on the weekend and walk around it. From the top of the reservoir, you had a clear view of both rivers and the NJ palisades.

- When the reservoir was first built, there weren’t many bildings around it, but by the 1850s, it was surrounded by brownstones. People were put off by its massive dark gray walls. It was a striking building, but not a very friendly one. They tried to soften it up by planting ivy on it.

- After a few decades of people complaining about the reservoir, it was demolished in 1898. They’d built more reservoirs in the meantime, and people seemed to really hate the reservoir aesthetically. It was estimated that it’d cost about $100,000 (more than $3 million) in today’s dollars.)

- If you go to the NYPL, though, there are some places where you can still see the stone granite of the old reservoir (I think it’s in the basement.)

- the original 1938 version of the Manhattan Detention Complex, more often referred to as “The Tombs,” where prisoners go to wait for hearings.

- Apparently Egyptian revival structures caught on in other cities, like Baltimore, a lot more than it did in NYC–for some reason NYers really found it aesthetically displeasing after the initial Egyptian Revival craze.

- Actual ancient Egyptian artifacts were also put in some major cities:

- Obelisks called “Cleopatra’s Needle” stand in London, Paris, and New York City–all three were about 1,000 years old when Cleopatra was alive, so their name is a misnomer, but they are ancient Egyptian obelisks. All three were gifts from the Egyptian government during the 19th century.

- I actually had only known about the NYC one, which is in Central Park by the Met, but when I looked it up, I realized the other two were also called Cleopatra’s Needle. I also hadn’t realized that the Central Park obelisk was a real, ancient obelisk–I’d assumed it was just inspired by ancient obelisks.

- I wanted to talk a little bit about the history behind these obelisks, since it says a lot about the history of European relations with places like Egypt.

- All three obelisks were gifts from Muhammad Ali Pasha, who was an Albanian Ottoman governor who basically ruled Egypt from 1805-1848. He was sent to take Egypt back from Napoleon, and once Napoleon’s troops left, he was able to maneuver into the position of Viceroy of Europe, and then ended up getting control of parts of Arabia, Upper and Lower Egypt, Sudan, and the Levant (the Levant is modern day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, a bunch of Turkey, Israel, and I think at some points parts of Greece?).

- So, the obelisk in Paris is one of two 3,000 obelisks that once stood at Luxor Temple. (The other one is still at Luxor.)

- The dynasty that Muhammad Ali Pasha set up ended up running Egypt until the revolution of 1952.

- So the reason why I got into all that detail is because he was a conquerer who took over Egypt–so it’s not like the obelisk was a gift from the Egyptian people, or something.

- In exchange for the obelisk, France was supposed to give him a French mechanical clock. However, after the obelisk had already been delivered to France, they discovered that the mechanical clock didn’t work. It may have been damaged in transit. Today, the clock sits in a clock tower in Cairo and still doesn’t work.

- There are 21 ancient obelisks that still stand. Here’s where they all are:

- Egypt has fewer than 5

- Rome has 13 (all taken during the time of the Roman empire)

- And the rest are scattered around between New York and Istambul

- A little history about the NYC obelisk: I saw some differing accounts (wikipedia says one thing, I found a different thing on PBS’s website)

- One story says that it was a gift after the Suez canal’s completion, and other places said that the US lobbied to get an obelisk after Paris and London got one.

- Obelisks called “Cleopatra’s Needle” stand in London, Paris, and New York City–all three were about 1,000 years old when Cleopatra was alive, so their name is a misnomer, but they are ancient Egyptian obelisks. All three were gifts from the Egyptian government during the 19th century.

- One note: when we were talking about Egyptian stuff a few weeks ago, I mentioned that people ground up mummies and used them as medicine. I’d thought it was a victorian thing, but apparently it was an earlier thing. People started doing it as early as either 1100 or 1300.

- In addition to an interest in genuine Egyptian obelisks, people were also interested in real Egyptian mummies. During the 19th century, mummy unwrappings became popular.

- In England, a surgeon named Thomas Pettigrew would host parties where people would come watch mummies be unraveled. He’d unwrap the mummy, then saw off part of their head, then prop up the mummy like they were still alive and try to scare people.

- These became really popular 19th century events–Pettigrew did 40 of them, for example.

- I have zero respect for Pettigrew–I find him detestable. In addition to trying to prove that the ancient Egyptians were white and commodifying the bodies of dead Egyptians, he also did things like display the severed, mummified head of an indigneous Australian named Yagan.

- Yagan had opposed colonial rule and was killed by bounty hunters. Pettigrew got the rights to use his head for 18 months. So he adorned Yagan’s head with cockatoo features and a headband. Then he’d display the head in front of a painting that showed the colonizers and indigenous people of Australia living together in hearmony.

- In the 19th century, Europeans started traveling to Egypt frequently

- In 1833, a French aristocrat and monk: “It would be hardly respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.”

- A few weeks after a traveler came back from Egypt, they’d invite people over for a mummy unwrapping. They’d have dinner and drinks, and then unwrap the mummy afterwards. Apparently the unwrapping would smell pretty bad, but maybe ppl were drink enough to not really care?

- This was generally a thing that rich people did–since they were the ones who had money to go to Egypt, or have friends who went to Egypt–but sometimes there were more public mummy unwrappings for the more general public to see.

- However, I will say that some experts say that mummy unwrappings weren’t actually as popular as people say they were, and that they were mostly done by scholars, etc.

- And actually, as far as I’ve been able to confirm, that’s correct. I mostly found articles describing mummy unwrappings as scientific or academic events.

- I found an 1850 article talking about how there were 8-10 million mummies in Thebes, and it talked about how anyone could travel to Egypt and then bring back a mummy. The article said: “The open doors of the tombs are seen in long ranges, and at different elevations, and on the plain, large pits have been opened, in which have been found 1000 mummies at a time.”

- It sounds like the scientific community started to push to preserve mummies for research purposes.

- I found an article from 1881 that described some American tourists finding an Egyptian princess’s tomb, and there’s just a throwaway line that says that the mummy “like most of the treasures of antequarian Egypt, was after a while carted away to the British Museum.” So it sounds like if tourists found mummies, at least around that time, they’d call experts to take a away the mummy, and then they might examine it.

- But I wanted to read a bit from one account I found, just as an example. This was originally printed in the New York Star in 1838 but seems to have been reprinted fairly widely:

- Antiquities from Egypt–An interesting scene lately took place at the Anatomical Theatre of the Washington Medical College, at Baltimore. It was the unwrapping of an Egyptian Mummy, from Memphis, presented by Commodore Elliot, of the Navy. The usual transverse wrapping of coarse muslin externally, and longitudinal wrapping of fine next to the shrivelled embalmed body, were observed. A skull in great preservation, not embalmed, and dug up by the Commodore himself, was also presented.

-

- The article then goes through a laundry list of other artifacts that were shown.

- I also read an August 1894 article in The Daily Morning Journal and Courier that mentions that as the century wore on, it was harder to get mummies to unwrap:

- The headline is : “Hark, From the Tombs” A Relic from Egypt–Three Thousand Years Old–Unwrapping a Mummy by the Scientific Society–Recently Came from Egypt and Was the Gift of Mrs. P.T. Barnum

- Of late years “the spoiling of the Egyptians” has been prevented by the government of that country as much as possible, and it has been constantly more and more difficult to procure for scientific purposes specimens of the ancient Egyptiam embalming art, and therefore the presentation to the scientific society of this city of a very fine mummy from Egypt, by Mrs. P. T. Barnum, was an event not to be lightly passed over. How Mrs. Barnum procured it is not known exactly but through some office of the American consul at Cairo or Alexandria, doubtless it was done.

- It’s nice to hear that Egypt was trying to reduce the number of mummies that were leaving the country, though by then it was pretty late I guess.

- The headline is : “Hark, From the Tombs” A Relic from Egypt–Three Thousand Years Old–Unwrapping a Mummy by the Scientific Society–Recently Came from Egypt and Was the Gift of Mrs. P.T. Barnum

- The interest in Egyptian beliefs about death became so great that in 1852, the 10th Duke of Hamilton insisted on being buried in the Egyptian style; he was mummified, then placed in an actual ancient Egyptian sarcophagus–which had once housed a princess whose name has been forgotten. He’d bought the sarcophagus 30 years before and had had carved out on the inside to fit his body, which was larger than its original inhabitant’s. He was then put in a Roman-style tomb at his estate in Scotland.

- In the 1840s, the Egyptian Book of the Dead was translated into English–that was the first modern translation. The book detailed different beliefs that the Ancient Egyptians had about death and the afterlife.

- Different occult groups, from the Masons to the Order of the Golden Dawn, ended up adopting different “Egyptian” practices. There’s a pretty funny looking picture of Aleister Crowley in like a pharaoh-type ritual headdress.

- And there were stories of Egyptian stuff being cursed, like this story from a 1896 article in the Hampshire Telegraph:

The mummy was that of a priest of Thetis and it bore a mysterious inscription [….] which was long and blood-curdling. It set forth that whosoever disturbed the body of this priest should himself be deprived of decent burial; he would meet with a violent death, and his mangled remains would be ‘carried down by a rush of waters to the sea’

- This mummy was purchased by an adventurer named Herbert Ingram from the British Consul in Luxor. Soon after, while hunting in Somalia, Ingram was trampled and attacked by an elephant. To read from an article from historyanswers.co.uk: “By the time his companions were able to reach his remains days later all but a handful of bones had been washed away by the rains.”

- So that’s a bird’s-eye view of 19th century Egyptomania.

- It’s by no means the only time that Americans and Europeans have been obsessed with Egypt–there was another huge resurgence in interest in Egypt in the 1920s, after Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in 1922.

- Interestingly, the 1920s also saw a HUGE resurgence in interest in Ouija, which is actually where we’ll pick back up next week.

Victorian Egyptomania Sources

Websites about Victorian Egyptomania

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_I_of_France

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aida

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnakhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Monument

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra’s_Needle

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra%27s_Needle_(New_York_City)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levant

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_of_Egypt

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luxor_Obelisks

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/egypt/raising/world.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_Revival_architecture

- https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2011/11/lost-egyptian-revival-croton-reservoir.html

- https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2011/07/lost-1838-egyptian-revival-tombs.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_Revival_decorative_arts

- https://archive.archaeology.org/online/features/egyptian_nyc/19thcentury.html

- https://www.ancient.eu/Egyptian_Obelisk/https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tombs

- https://mountauburn.org/egyptian-revival-gate/

- https://www.dukeupress.edu/Egypt-Land/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paschal_Beverly_Randolphhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Go_Down_Moses

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/egyptian-building

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/victorian-party-people-unrolled-mummies-for-fun

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oujda

- https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/355673/etymology-and-pronunciation-of-ouija

- https://www.historyanswers.co.uk/people-politics/victorian-egyptomania-how-a-19th-century-fetish-for-pharaohs-turned-seriously-spooky/

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/mummy-unwrapping-parties

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_era

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgian_era

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gothic_Revival_architecture

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmilla

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptomania

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egyptian_Hall

- https://georgianlondon.com/post/55869874064/lost-london-the-egyptian-hall

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Nevil_Maskelyne

- https://flashbak.com/joseph-fabers-freakish-talking-head-haunts-uncanny-valley-1846-57136/

- https://archive.org/details/1876MaskelyneModernSpiritualism

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/mummy-unwrapping-parties

- https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2009/06/14/when-the-citys-water-supply-came-from-42nd-street/

Historical articles and advertisements about Victorian Egyptomania

-

A Mummy Unwrapped Alexandria gazette and advertiser. June 17 1824 Image 2

-

A Palace Tragedy Steuben Republican Wed Dec 8 1886

-

Antiquities from Egypt The native American. Washington City i.e. Washington, D.C. 1837-1840- December 22 1838- Image 4

-

Argus and Patriot Wed Dec 15 1897

-

Broad Views of a Woman. The Wichita daily eagle. September 30 1890- Page 6- Image 6

-

Great Find of Egyptian Relics The Lake Charles echo. October 22 1881. Image 2

-

Hark From The Tombs The Daily Morning Journal and Courier Mon Aug 20 1894

-

Monsters to Order The Roanoke daily times. February 20 1896 Page 2 Image 2

-

Mummies of Egyptian Kings. The County paper. September 09 1881- Image 3

-

Mummy Unwrapping The Knoxville Register Sat May 25 1850

-

Ramses the Great St. Landry democrat. January 07 1888 Image 2

-

Rarest of June Roses. The climax. Kentucky. July 18 1888- Image 1

-

Rather Ancient The Caldwell tribune. April 09 1898 Image 1

-

Some Ones Baby Once Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express Sat Jan 14 1893

-

Story of an Ancient Statue Wessington Springs herald. April 29 1887 Image 3

-

That Mummy The daily crescent. June 27 1850 -Morning- Image 3

-

The Obelisk Kings. Iron County register. September 15 1881- Image 6

-

The Presbyterian of the South – Southwestern Presbyterian, Central Presbyterian

-

Southern Presbyterian. Atlanta Ga. 1909-1931 March 03 1909 Page 4 Image 8

-

The Preserved Dead. The National tribune. April 02 1891-Page 3-Image 3

-

The Black Hills Weekly Journal Fri Feb 7 1890

-

Turner County herald. September 16 1886 Image 4

-

Unique And Cosy The Evening Express Sat Aug 5 1893

-

Unrolling A Mummy Sunbury American. Sunbury, Pa. 1848-1879- June 15 1850 Image 2

-

Unwrapping a Mummy Sunbury American. Sunbury, Pa. 1848-1879- June 15 1850- Image 2

-

Unwrapping an Egyptian Mummy Weekly expositor. Brockway Centre Mich. 1882-1894 April 21 1887 Image 3

-

Unwrapping Mummy Postponed for Year-Evening star. Washington D.C.- 1854-1972- January 23 1924- Page 15- Image 15

-

Unwrapping of Mummy Filmed Evening star.-Washington, D.C.-1854-1972 December 31 1935 Page B-9 Image 25

-

Unwrapping A Mummy The San Francisco Examiner Sun Sep 8 1895

-

Unwrapping A Mummy Vermont Journal Sat Sep 7 1867

-

X-Ray Photographs Used by Scientists-New Britain herald. New Britain Conn.- 1890-1976- December 17 1923 Page 11 Image 11

-

X-Ray Pictures of Mummies Taken Evening star.-Washington, D.C.- 1854-1972- December 14 1923 Page 61 Image 61

Books consulted RE: Victorian Egyptomania

- A History of Egyptian Mummies By Thomas Joseph Pettigrew:

https://books.google.com/books?id=1VwzAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Check out the shownotes for the rest of the series to see all of the sources used.

Listen to the rest of the Ouija board series:

- Ouija Boards Part 1 – Planchette and Automatic Writing

- Helen Peters and Ouida / Invention (Ouija Boards Part 2)

- William Fuld (Ouija Boards Part 3)

- 19th Century Ouija Board Stories / Early Ouijamania (Ouija Boards Part 4)

Don’t miss our past episodes:

- The Renwick Ruin:

- Playing the Ghost in 19th Century Australia

- Investigating the Hawthorne Hotel: